Author’s Note: Updated from a previous publication.

We can all agree: Accreditation is something all higher education officials acknowledge is necessary, but the accreditation stress that goes along with it is something they’d love to do without.

Each accrediting body has its own standards and quality indicators. They have their own policies and procedures which can vary widely. However, one thing that’s common across every accrediting body a site visit, where a review team spends a few days on campus (or virtually) conducting interviews, verifying information, and making recommendations regarding how well the institution measures up to standards.

Regardless of the accrediting body, the site visit is both expensive and exhausting. With very few exceptions, faculty, staff, and administrators shout for joy when they see a site review team leave campus and head for the airport.

Accreditation Stress is Real.

In many instances, staff involved in the accreditation process focus so much on preparing for the site visit they aren’t ready for the emotional or physical toll that it can take on them. Moreover, the stress usually doesn’t end when the site review team leaves. My experience in accreditation over the past 10 years has confirmed there’s a need for this kind of information, and yet it’s a topic I’ve never seen addressed at conferences or in professional literature.

Accreditation-related stress and anxiety are real. You might be able to function, and you may be able to hide it from others. But, how do you know if it’s starting to get the best of you? And what can you do about it?

Red Flag Alert: Some Signs the Stress is Negatively Impacting Your Life

You’re surviving, but you’re not thriving. You may be making it through each day, but the quality of your life is suffering. You’re not enjoying the things that used to make you happy. You feel guilty about taking the time to watch a sunset or to read a book. Every waking moment is spent thinking about the site visit.

Those lights in your brain just won’t shut off. You can’t sleep, even though you feel exhausted. You’re worn out physically and mentally, but you can’t allow yourself to take even a few hours off to rest.

You’re numb inside. You have no appetite and aren’t eating. You’ve even managed to shut down your emotions. It’s like you’ve gone on auto-pilot and feel like a robot.

You feel empty, like there’s a gaping hole inside. But even though the emptiness isn’t from hunger you binge eat everything in sight. And then you still look around for more because you still have that huge gaping hole that just can’t seem to be filled.

You become obsessed with every detail, no matter how minute it may seem. It’s those little foxes that spoil the vine. You’re determined that you’re going to make sure NOTHING is overlooked.

You come to believe that you are ultimately responsible for the success of the site review. If you’re honest with yourself, you don’t think others are as committed to success as you are. The little voice inside you says, “If you want something done right, you’ve got to do it yourself!”

You start to resent others who don’t seem as stressed out as you are. While you hate feeling like you have the weight of the world on your shoulders, you refuse to delegate responsibility to others and then you get mad when you hear that they went to a movie or a concert over the weekend.

Drink the Stress Away: You may hear yourself saying, “I just need to take the edge off” or “I just need to relax for a while.” Having one glass of Chardonnay is one thing but knocking back five tequila shots in 30 minutes is another.

Ups and Downs: You may self-medicate by taking a pill or two to help you sleep because even though you’re exhausted, you’re wired due to all the stress.

Caffeine overload: You may guzzle coffee, soda, or Red Bull throughout the day (or night) because, “I’ve got to keep going for just a little while longer.”

Shop ‘til Your Fingers Drop: On a whim you may go on a shopping spree and spend a ton of money on things you probably didn’t really need. Not at a brick and mortar store or mall—that would be far too self-indulgent. Instead, you likely visited Zappos or Amazon, where you could remain close to your computer and be right there to respond to an urgent email should one land in your Inbox.

Keep Setting the Bar Higher: You set impossible standards for yourself to meet and then criticize yourself endlessly when you don’t meet them. It’s like you’re obsessed with proving something to others—and to yourself. Except that you’re never satisfied with your performance, even when you do things well.

Slay the Dragon: You plan things down to each minute detail, leaving no stone unturned. You review things in your mind, over and over again. Sometimes you obsess about forgetting something. You’re determined to emerge victorious, regardless of the personal cost.

Accreditation Stress: The Gift that Keeps on Giving

Think the stress of getting ready for a site visit only affects you? Think again. If you have close friends, a life partner, or children, they are affected as well. It’s possible that your furry buddies at home can even detect your anxiety. You’ll know if your stress is out of balance if you hear a loved one say, “I miss you!” “I HATE your job!” or “Will this ever end?”

Moving from Surviving to Thriving: How to Manage Your Stress in a Healthy Way

Even Superman struggled at times with Kryptonite. However, he found ways to adapt and overcome those challenges, and so can you. While an accreditation site visit always leads to a certain level of stress, there are things you can do to minimize the anxiety. For example:

Prepare ahead of time: It may sound simplistic, but getting a jumpstart on the process reduces a lot of stress. If you don’t start on the process until 6 or 8 months before the site visit, you are putting yourself squarely in the crosshairs of some serious stress and anxiety.

Ideally, quality assurance should be an integral part of every program. There really shouldn’t be any significant scrambling or looking for data. Your institution should already be reviewing, analyzing, looking for trends, and making data-driven decisions to improve programs on a continual basis. You should plan on starting your self-study report (SSR) no later than 18 months prior to a scheduled site visit. The more you delay this timetable, the higher your stress level will be. Guaranteed.

Hire a consultant: Let’s face it–not everyone has a lot of expertise when it comes to writing self-study reports, gathering evidence, and preparing for site visits. In many institutions, departments are understaffed and often wear multiple hats of responsibility. Most institutions don’t have to deal with accreditation matters on a regular basis. Therefore few have a high level of confidence in that area.

In some schools, new faculty coordinate a site visit because more seasoned faculty refuse to do it. This is wrong on so many levels, and yet it’s a frequent occurrence. An experienced consultant could provide the kind of guidance and support that may be needed. The institution doesn’t incur the expense of paying for someone’s full-time salary, benefits, or office space. In this age of budget cuts, hiring an independent contractor can actually save money.

Provide faculty/staff training: Letting others know what to expect and getting them on board early on will greatly reduce anxiety for everyone. Plan a kickoff event, and then schedule periodic retreats/advances. Create a solid communication protocol and stick with it. When team members are fully informed and are active contributors to the process, the stress is reduced for everyone.

Delegate to others as much as possible: It’s important to have a project manager/coordinator for every major project, and that includes accreditation site visits. However, that does NOT mean that this one person needs to take on the bulk of the responsibility—quite the contrary. Instead, that person should serve as a “conduit” who facilitates the flow of information between internal and external stakeholders. That person should also play the primary role in delegating tasks to appropriate personnel. He or she maintains a schedule so that tasks are completed on time.

It’s OK to talk about it: Know that a certain amount of stress and anxiety are normal reactions to accreditation site visit preparation, but it doesn’t have to be overwhelming. Don’t be afraid to talk with your colleagues and leadership about your stress level. It’s entirely possible that others share your feelings—it might be helpful to start a small informal support group. Getting together one day a week for lunch works wonders.

Be upfront with your friends and loved ones: Prepare family and friends ahead of time. Help them to know what to expect. Include them in the celebration once it’s over. Your children, significant other, and close friends may not be writing the self-study report or creating pieces of evidence. Your support system also plays an important role in the site review process behind the scenes.

Be kind to yourself: This may sound silly but it’s really important. Purposely build one nice thing into your personal calendar each day. It may be taking a walk, working out, or reading for pleasure for 30 minutes. Regardless what you choose, it’s crucial that you make this a part of your schedule.

Be ready when it’s over: You may find that you can hold yourself together from start to finish, but then after the site review team packs up and leaves your institution you have a feeling of not quite knowing what to do with yourself. What you’ve focused all your energy on for 18 months is suddenly over. This can result in your emotions taking a deep dive—and it can last for several weeks.

You can greatly reduce this by planning a combination of fun activities and work activities for your next four weeks after the site visit. You’ve been functioning within a very structured paradigm for several months. However, if you suddenly have nothing to do it will likely lead to additional anxiety so it’s best to transition back slowly.

The bottom line is that while accreditation stress is definitely real, it doesn’t have to get the best of you or your team.

###

About the Author: A former public school teacher and college administrator, Dr. Roberta Ross-Fisher provides consultative support to colleges and universities in quality assurance, accreditation, educator preparation and competency-based education. Specialty: Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP). She can be reached at: Roberta@globaleducationalconsulting.com

Top Graphic Credit: Luis Villasmil on Unsplash

Regardless of whether a site visit is conducted on campus or virtually, there’s something very common:

Regardless of whether a site visit is conducted on campus or virtually, there’s something very common:

Just as you wouldn’t decide a month in advance that you’re going to run a marathon when the farthest you’ve been walking is from the couch to the kitchen, it’s to an institution’s peril if they don’t fully prepare for an upcoming site visit regardless of whether it’s onsite, virtual, or hybrid.

Just as you wouldn’t decide a month in advance that you’re going to run a marathon when the farthest you’ve been walking is from the couch to the kitchen, it’s to an institution’s peril if they don’t fully prepare for an upcoming site visit regardless of whether it’s onsite, virtual, or hybrid.

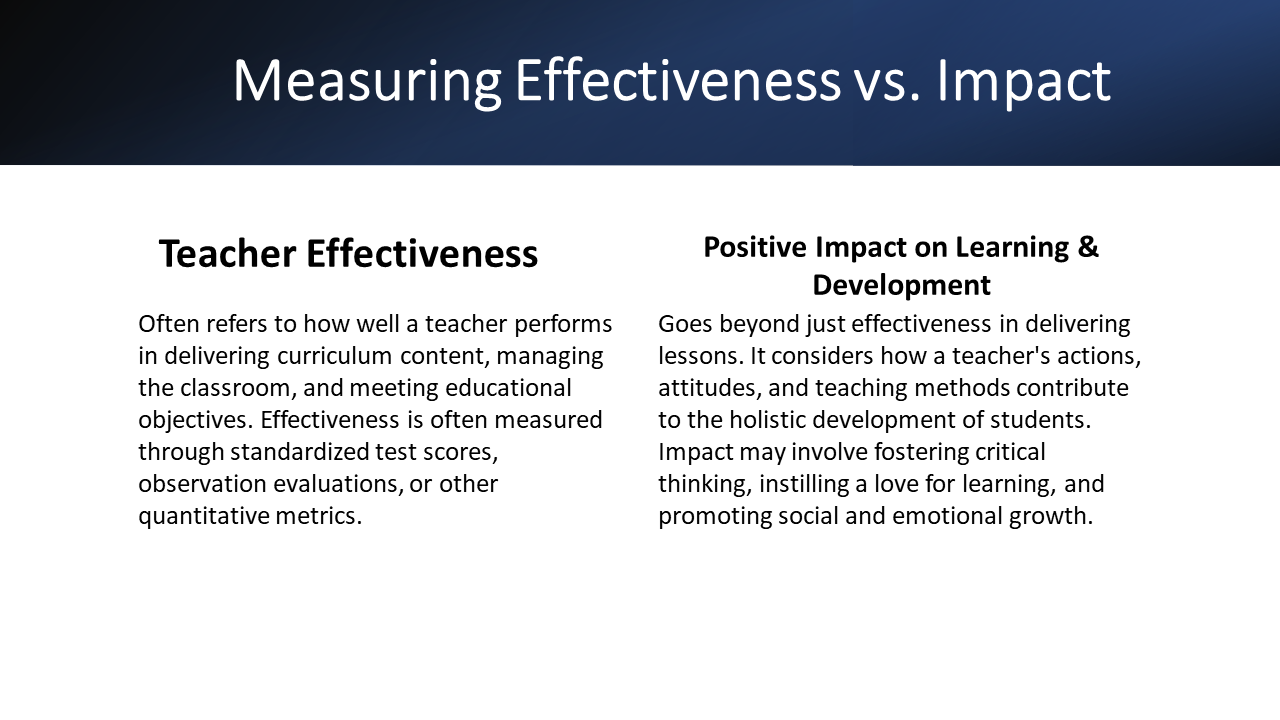

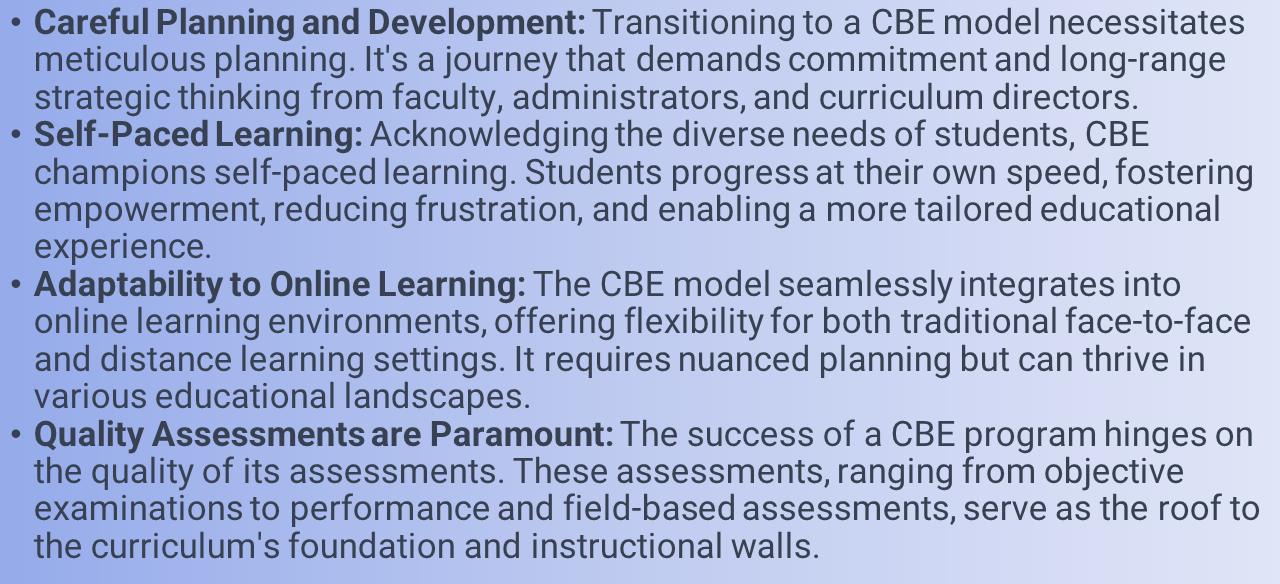

In a CBE, students showcase their knowledge and skills through a variety of high-quality formative and summative assessments. This approach shifts the focus from traditional testing to a more comprehensive evaluation of a student’s true understanding and application of concepts.

In a CBE, students showcase their knowledge and skills through a variety of high-quality formative and summative assessments. This approach shifts the focus from traditional testing to a more comprehensive evaluation of a student’s true understanding and application of concepts. Initiating CBE at the college or university level requires a comprehensive institutional commitment. This commitment involves a paradigm shift in the faculty model, changes in registration and scheduling processes, and adaptations to student support services. Here are a few practical tips to navigate these challenges:

Initiating CBE at the college or university level requires a comprehensive institutional commitment. This commitment involves a paradigm shift in the faculty model, changes in registration and scheduling processes, and adaptations to student support services. Here are a few practical tips to navigate these challenges: While the transition to Competency-Based Education may present challenges, the benefits are substantial. It provides a pathway for institutions to meet the needs of a diverse student population, acknowledging the rich experiences that learners bring to the table. Moreover, the flexibility of CBE can be a strategic advantage in attracting a broader range of students.

While the transition to Competency-Based Education may present challenges, the benefits are substantial. It provides a pathway for institutions to meet the needs of a diverse student population, acknowledging the rich experiences that learners bring to the table. Moreover, the flexibility of CBE can be a strategic advantage in attracting a broader range of students.