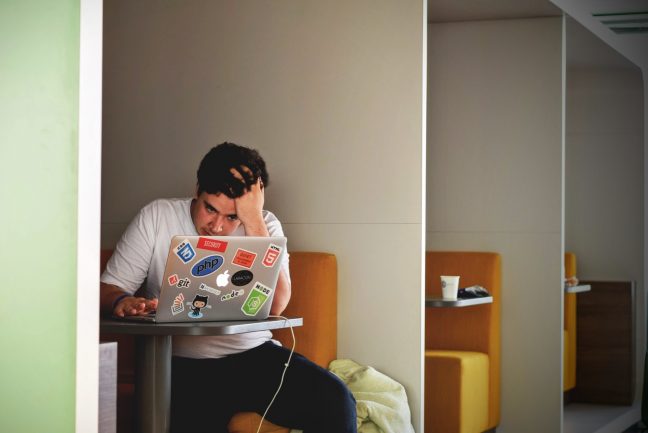

In the realm of higher education, quality assurance and institutional effectiveness are paramount. Internal and external stakeholder groups, including students, faculty, alumni, employers, and community members play a pivotal role in this process. Their active involvement not only ensures transparency but also significantly contributes to accreditation efforts.

It seems that nearly everyone in higher education is aware of the need for stakeholder involvement–or say they are–but very few actually use it effectively. In this post, I delve into the importance of stakeholder involvement in higher education and provide some practical advice for colleges and universities to harness it effectively.

Why Stakeholder Involvement Is Vital

Engaging stakeholders brings diverse perspectives and valuable insights to the forefront. Here’s why their involvement is critical:

Enhanced Accountability

Stakeholder involvement fosters transparency and accountability within institutions. It ensures that decisions align with the needs and expectations of those they serve. As members of the higher education community, we often develop “tunnel vision” and become so entrenched in our everyday institutional bubble that it’s possible to lose our perspective. As a result, we sometimes don’t consider things from a lens outside of our own. That’s where stakeholder groups can be so valuable to the accountability process.

Continuous Program Improvement

Regular feedback from stakeholders helps colleges and universities identify areas for enhancement. This feedback loop leads to ongoing program improvements, benefiting students and the broader community. To that end, institutional accreditor Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) prompts university personnel to ensure that appropriate internal and external constituents and stakeholders are involved in the planning and evaluation process as part of their overall institutional planning and effectiveness model.

Accreditation Support

Accrediting bodies often require evidence of stakeholder involvement. Comprehensive records of these interactions streamline the accreditation process and bolster institutional credibility. That doesn’t mean, however, that we should just create an advisory board of some kind in name only. Nor should we hold our obligatory annual meetings for the purpose of simply checking a box and moving on. If institutions build a culture of continuous program improvement rather than a culture of compliance, they will realize just how important stakeholders can be to their regulatory success.

Initiating and Optimizing Stakeholder Involvement

Here are practical steps for college and university personnel to initiate and optimize stakeholder involvement:

Identify Your Key Stakeholders

Identify the primary internal and external stakeholders relevant to your institution, including students, part-time and full-time faculty, alumni, employers, business and industry representatives, and community organizations. Students, of course, should be viewed as the most critical stakeholder in higher education. To underscore the importance of this group, the Higher Learning Commission adopted it as Goal #1 in its Evolve 2025: Vision, Goals, and Action Steps. It’s essential to select individuals who genuinely want to help you improve your institution. It’s also important to build a cadre of stakeholders who represent a variety of backgrounds and perspectives.

Set Clear Objectives

Determine the specific outcomes you need from your stakeholder groups. Are you seeking input on curriculum development, program evaluation, or community engagement initiatives? Having a clear purpose guides your efforts. For example, in its 2020 Guiding Principles and Standards for Business Accreditation, the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) specifies that stakeholders should play a central role in developing and implementing a program’s strategic plan, in its scholarship, and in its quality assurance system.

Establish Communication Channels

Create multiple communication avenues with stakeholders, such as surveys, focus groups, advisory committees, and regular meetings. Ensure these channels are accessible and user-friendly. Maintaining effective communication and collaboration with stakeholder groups is considered to be part of an essential team of administrators that brings together and allocates resources to accomplish institutional goals, according to the Association for Biblical Higher Education (ABHE), an accreditor for faith-based institutions.

Meet Regularly

Meeting with stakeholders at least once a year is crucial. Consider more frequent interactions, such as quarterly or semi-annual meetings, to maintain engagement. Establishing positive relationships takes time, and this requires seeing stakeholders more than just once per year. Some institutions invite stakeholders to a monthly virtual meeting, supported by one or two onsite meetings. To encourage attendance and keep the momentum going, consider the value of variety: Invite students to come and speak or interact with advisory board members. Don’t overdo it but try to include at least one fun icebreaker or activity in each meeting. And above all else: Whenever possible, provide food. Educators have known about this for many years, and it’s still true today: If you feed them, they will come.

Share Data

Share relevant data and information with stakeholders, including enrollment figures, student achievement data, and institutional goals. Providing context allows stakeholders to make informed recommendations. And don’t just sugarcoat everything–be real with your stakeholders. If you can’t trust them with data that may be less than desirable, why are they on your advisory board?

Establish a Positive Environment

Foster an open and inclusive environment where stakeholders feel valued and heard. Encourage constructive feedback and respect dissenting opinions. Hopefully, each member of the stakeholder group was selected with care because of the value they bring to the conversation. Assuming that’s the case, each person should walk away from meetings feeling as though their presence and participation mattered. It’s the job of the institutional leader to ensure that happens.

Create a Documentation Framework

Keep detailed records of stakeholder interactions, including meeting agendas, minutes, recommendations, and action items. These records serve as tangible evidence for accreditation purposes. We’ve all heard the saying, “If there’s no photo, it didn’t happen!” The same thinking applies with stakeholder meetings. If there’s no detailed record, it’s really the same as a meeting never taking place. All documents should contain enough details that someone outside the institution (such as an accreditor) could review them and understand who the members are, what the group’s purpose is, how often they meet, what they do, and how the institution’s personnel act on their recommendations. Pro tip: Create a standard template for meeting agendas and minutes, and store all documents in a secure, university-approved cloud platform in an organized manner. Never store these items on a single user’s laptop.

Using Stakeholder Involvement Effectively

Simply hosting an annual stakeholder meeting to check off a compliance box isn’t good enough. Higher education personnel must weave their input into all facets of their institutional or programmatic structure. The importance of this is emphasized by the 2023 standards adopted by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, where stakeholder involvement is featured in multiple standards. To maximize the benefits of stakeholder involvement, I recommend following these guidelines:

Act on Feedback

Don’t just collect feedback; act on it. Use stakeholder recommendations to drive meaningful change within your institution, demonstrating a commitment to improvement. For example, educator preparation accreditors such as the Association for Advancing Quality in Educator Preparation (AAQEP) and the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP) both have expectations for utilizing input from teacher candidates, alumni, employers, P-12 partners, and the like.

Evaluate Impact

Regularly assess the impact of changes made based on stakeholder feedback to ensure ongoing positive progress. This is an essential component to your quality assurance system and to a continuous program improvement model. Advancing academic quality and continuous improvement are at the core of accreditation, according to the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA).

Engage Diverse Voices

Ensure your stakeholder group represents a diverse range of perspectives, leading to more innovative and well-rounded solutions. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) emphasizes the need for multiple voices to be heard in its more recent set of Core Competences for Professional Nursing Education.

Communicate Outcomes

Keep stakeholders informed about the outcomes of their input. Sharing how their feedback has shaped decisions and improvements underscores the value of their involvement. This goes back to helping all members feel valued, heard, and respected. It also renews their commitment to your organization and their role in advancing institutional goals.

Maintain an Active Feedback Loop

Continuously refine your stakeholder involvement processes based on feedback to make the collaboration more effective and efficient. In other words, the model should be organic and evolve over time as needs change. The mission, vision, and objectives of stakeholder groups should be revisited periodically in order to gain maximum benefit.

Conclusion

Incorporating stakeholder involvement into higher education quality assurance is not just a best practice; it’s a necessity. By actively engaging stakeholders, colleges and universities can ensure their programs remain effective, relevant, and aligned with community needs. Moreover, documenting these interactions provides valuable evidence for accreditation, further enhancing institutional credibility.

###

About the Author: A former public school teacher and college administrator, Dr. Roberta Ross-Fisher provides consultative support to colleges and universities in quality assurance, accreditation, educator preparation and competency-based education. Specialty: Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP). She can be reached at: Roberta@globaleducationalconsulting.com

Top Photo Credit: Campaign Creators on Unsplash