We need a paradigm shift in higher learning. For over a century, the Carnegie Unit has been the cornerstone of American education, providing a time-based standard for student progress. However, as the landscape of education evolves, the limitations of this model become apparent, prompting educators to explore innovative alternatives. One such model gaining significant traction is Competency-Based Education (CBE). In this post, I’ll delve into the merits of CBE and offer some practical tips for higher education professionals looking to pilot this transformative approach.

Rethinking Education in the 21st Century

The traditional education model often propels students forward collectively, irrespective of individual learning paces or abilities. The disruption caused by events like COVID-19 has underscored the need for a more adaptive and personalized approach. We know that each learner is different, and they come with a variety of learning needs as well as life and work experiences. For too long, we’ve used a cookie cutter, one-size-fits-all approach to teaching and learning — particularly at the higher education level. Enter Competency-Based Education, a paradigm that requires learners to demonstrate their understanding and skills through rigorous assessments rather than mere attendance. It also requires faculty members, administrators, and other staff to rethink their roles and how they support students through their academic journey.

Unveiling the Essence of CBE

Competency-Based Education isn’t about taking the easy route; it’s about embracing a different and more effective methodology. Instead of passively absorbing information, students are challenged to showcase their knowledge and abilities through high-quality assessments. This approach is inherently standards-based and is built on evolving educational and/or industry-specific standards. This is far different from what most faculty members are used to, when they alone decide what content to teach in their classes, how students will meet their expectations, and the pace at which students may progress through a course.

Key Principles of Competency-Based Education

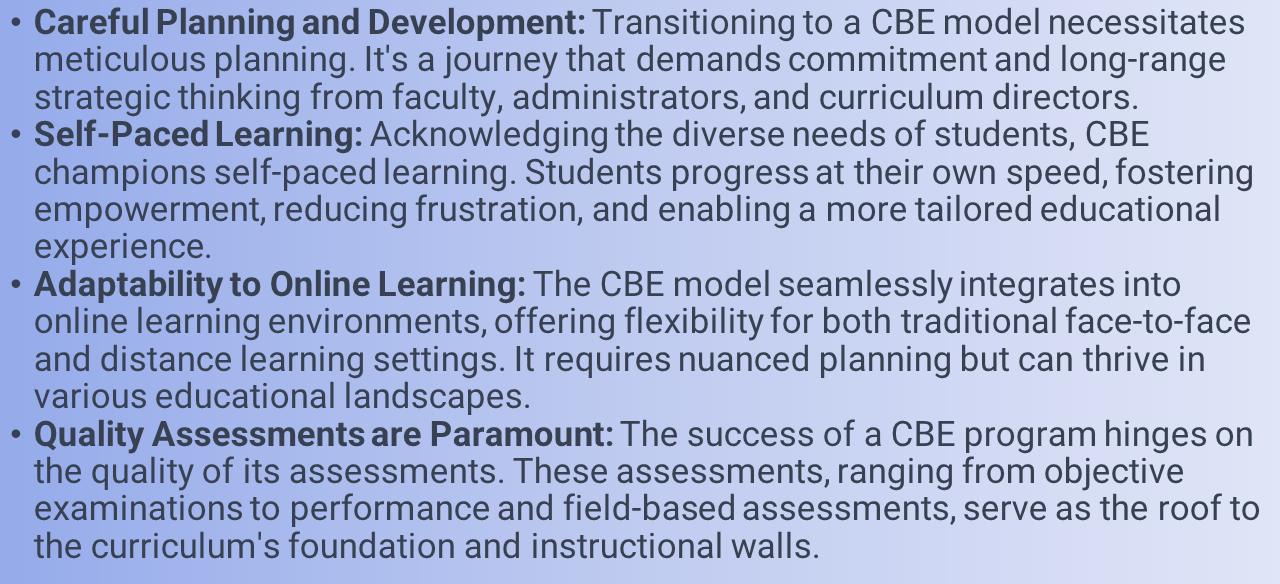

Traditional learning and CBE learning share a common goal of wanting students to be successful. It’s how they meet that goal that’s different. Here are some key “big picture” ways where a competency-based model is quite different from a traditional course-based model:

A Paradigm Shift: Tips for Piloting CBE in Higher Education

I’ve presented at conferences on this topic, and multiple times have been approached by a college dean or department chair who was interested in bringing the CBE model to their campus. Few realize that changing to this model — either retrofitting an existing program or creating a program from scratch — require a considerable paradigm shift not only to academics, but to infrastructure services (i.e., enrollment & admissions, registrar, bookstore, academic advising, etc.). I even had a dean once pull out a pen and small tablet out of her purse, waiting for me to give her three easy steps to CBE, as if it was a biscuit recipe. The truth is, competency-based education is a complex approach to teaching and learning. Once it’s in place, the payoff can be tremendous — but stakeholders must understand the cultural changes that must take place in order for CBE to become a long-term reality within their institutions.

Here are a few key tips for launching CBE at the higher education level:

A Long-Term Commitment to Student Success

Competency-Based Education is not a quick fix, but a powerful, long-term solution to enhance student learning, achievement, and satisfaction. It truly is a paradigm shift in higher learning. I think it’s time to take the leap into a future where education adapts to the needs of the learner.

###

About the Author: A former public school teacher and college administrator, Dr. Roberta Ross-Fisher provides consultative support to colleges and universities in quality assurance, accreditation, educator preparation and competency-based education. Specialty: Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP). She can be reached at: Roberta@globaleducationalconsulting.com

In a CBE, students showcase their knowledge and skills through a variety of high-quality formative and summative assessments. This approach shifts the focus from traditional testing to a more comprehensive evaluation of a student’s true understanding and application of concepts.

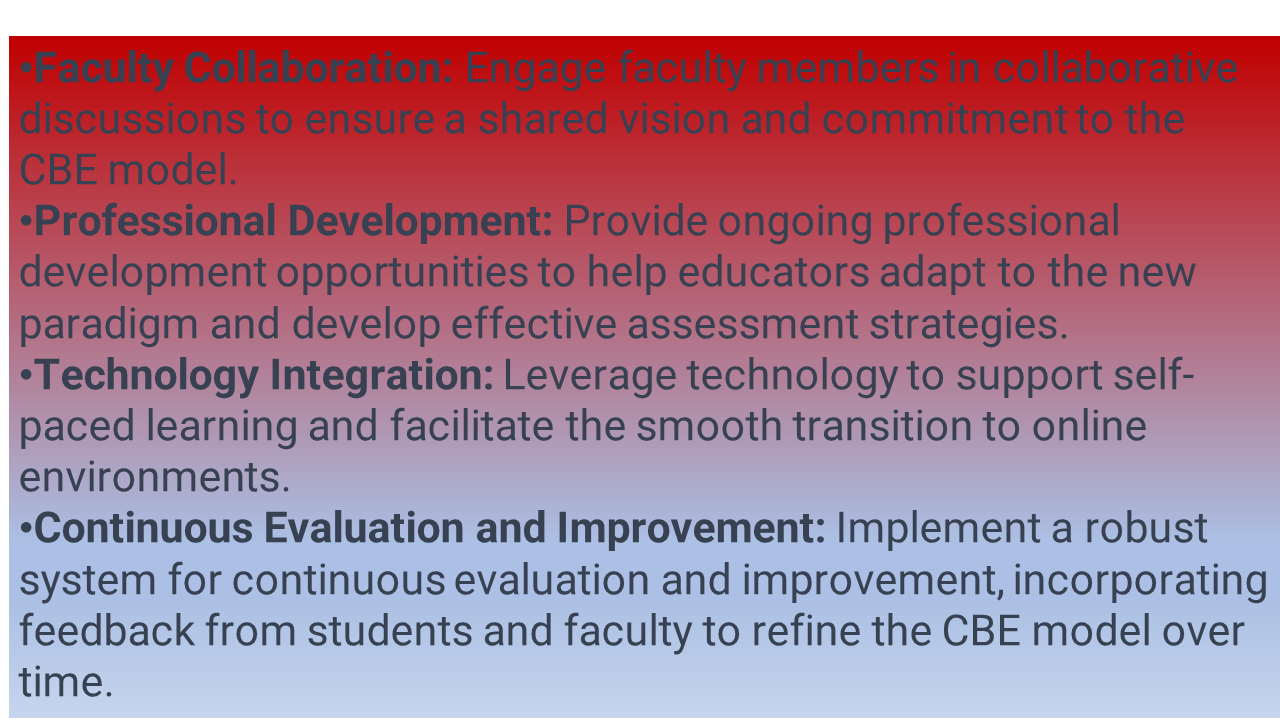

In a CBE, students showcase their knowledge and skills through a variety of high-quality formative and summative assessments. This approach shifts the focus from traditional testing to a more comprehensive evaluation of a student’s true understanding and application of concepts. Initiating CBE at the college or university level requires a comprehensive institutional commitment. This commitment involves a paradigm shift in the faculty model, changes in registration and scheduling processes, and adaptations to student support services. Here are a few practical tips to navigate these challenges:

Initiating CBE at the college or university level requires a comprehensive institutional commitment. This commitment involves a paradigm shift in the faculty model, changes in registration and scheduling processes, and adaptations to student support services. Here are a few practical tips to navigate these challenges: While the transition to Competency-Based Education may present challenges, the benefits are substantial. It provides a pathway for institutions to meet the needs of a diverse student population, acknowledging the rich experiences that learners bring to the table. Moreover, the flexibility of CBE can be a strategic advantage in attracting a broader range of students.

While the transition to Competency-Based Education may present challenges, the benefits are substantial. It provides a pathway for institutions to meet the needs of a diverse student population, acknowledging the rich experiences that learners bring to the table. Moreover, the flexibility of CBE can be a strategic advantage in attracting a broader range of students.